Sino-Romanian Relations

--From the First Ponta’s government to Klaus Werner Iohannis’s victory in the presidential elections

Abstract: The relationship between Romania and China is an ancient one, despite the geographic distance and the difference in size of the two countries. During the cold war, the relationship reached its apex because China’s conflict with the Soviet Union coincided with Romanian diffidence towards Moscow. After the events of 1989, however, the two countries undertook different paths. China’s rise allowed Beijing to become a global player in the international arena, while Romania limited its foreign policy to the Euro-Atlantic domain. Nevertheless, the economic crisis that is currently affecting Europe pushes the Balkan country to look for new partners. In such a scenario, China may represent a strong option, especially in the economic field. Until now, however, Bucharest policies towards Beijing are characterized by twists and turns. Uncertainty prevails among the Romanian foreign policy decision-makers on the matter. This paper, therefore, aims to understand the possible choices of Romania with regard to China after the election of Klaus Iohannis to the presidency and the Chinese attitude in front of the new Romanian leader.

Key Words: Sino-Romanian Relations Ponta Government Trade and Investment Relations Political Relations

History and Present

Introduction: a brief history of Sino-Romanian relations

Sino-Romanian relations dated back to the 19th century, when King Carol I notified Romania’s independence to the Chinese Emperor Guangxu, which replied through Prince Kong and declared his felicitations for the event. Since then, the relations between the two countries remained negligible. Indeed, the geographic distance and both countries’ internal troubles played a decisive role in stopping any chance to improve the bilateral relationship for almost 70 years.In fact, the Sino-Romanian bilateral relationship started during the 1950s thanks to the common membership to the Soviet bloc at the beginning of the Cold War. The rise of the Sino-Soviet split at the end of that decade entailed a more pronounced approach between Beijing and Bucharest. After much hesitation, the Romanian government led by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej decided to launch a policy of national communism, taking some distance from Moscow and slowly getting closer to the People’s Republic of China. Gheorghiu-Dej’s successor, Nicolae Ceausescu, was determined to undertake autonomous external relations and strongly pursued a policy of friendship towards China. For two decades, political and economic relations between the two countries increased continuously: Zhou Enlai’s open support to Romania’s independence in the wake of Prague’s events in 1968, Bucharest’s role in the Sino-US approach, Ceausescu’s triumphal visit to Beijing in 1971, all testify the intensity of the relationship. Trade ties reached their apex on 1979. Since then, Romania and China undertook different paths: Ceausescu decided to pay back Romania’s huge external debt, forcing the country in a difficult economic position, while the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping pushed the People’s Republic to a path of reforms and opening to external markets. During the 1980s, the bilateral relationship remained cordial on a political and diplomatic level, but Romania was not an important economic partner for China anymore.

The downfall of Ceausescu’s regime in December 1989 definitely modified the bilateral relationship. Actually, the conditions in order to improve the relationship were good. Beijing immediately recognized the new Romanian government and the Chinese press outlined the mistakes made by Ceausescu, who had lost the right Marxist way. During the early 1990s a flow of thousands of Chinese migrants reached Central Eastern Europe, Bucharest included, building a stable community in the capital city. Contrary to other CEE countries, Romania did not question the “One-China Policy”, avoided any formal contacts with the Dalai Lama or Taiwan, and was not interested in the “human rights” issue. The first Romanian President after Ceausescu, Ion Iliescu, travelled to Beijing on January 1991, signing several agreements and reaching a grant of $20 million. Nevertheless, the Balkan country turned its eyes to West, therefore following a general diplomatic trend that interested the entire Eastern Europe.

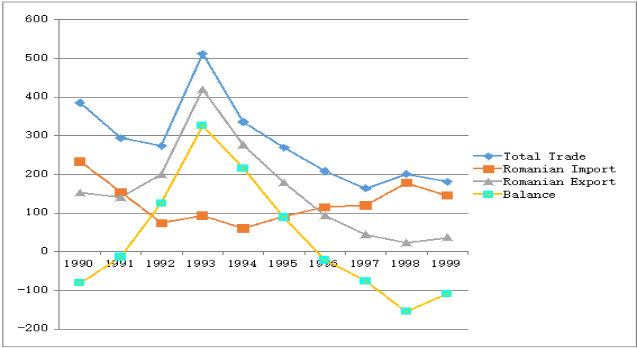

The Trade relations confirmed the new orientations of the Romanian foreign policy. The graphic no. 1 shows that Sino-Romanian trade decreased in the period 1990-1992. Import from China (that it was experiencing some years of economic recession until 1992), in particular, felt down, while Bucharest’s export raised exponentially until 1993, originating a positive trade balance for the Balkan country. Starting in 1994, however, Romanian exports continually decreased until 1998, while imports from China slowly recovered and the trade balance became positive for Beijing once again in 1996. Actually, this trend depended on a bilateral agreement reached prior to 1990 that envisaged Romania’s reimbursement of Chinese credited matured during the years before 1989. Moreover, in 1997 Beijing terminated the custom preferential treatment allowed to the Romanian exports. This event combined with the scarce dynamic of Romanian enterprises, their lack of knowledge of China’s market and culture, as well as the poor quality of their products, provoked the crisis of Bucharest’s exports to China.

Graphic 1. China-Romania trade, 1990-1999. $ Million.

Data source: Comisia Naţionala pentru Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 1996, pp. 622-623; Comisia Naţionala pentru Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 1999, p. 558; Institutul Naţional de Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 2001.

During the 2000s, the astonishing growth of China’s economy led to the widening of the gap between Romanian imports from and exports to the Asian giant. In the first decade of the 21st century, imports from China continually increased with few exceptions in 2007 and 2009 due the booming of the global economic crisis, which temporarily affected Beijing’s exports. From one hand, mainly mechanic products compose Romanian exports, while the weight of the steel industry and metallurgy seems decreasing. On the other hand, mainly consumer goods and textiles compose imports from China. According to the Romanian data, in 2010 the total turnover reached an apex of almost € 3 billion. The disequilibrium of the balance of trade, however, is strongly burdening the economic relationship. Bucharest expressed its concerns and frustration several times, calling for some measures to re-equilibrate the trade exchanges. In fact, nobody has been able to elaborate such measures that, considering the different economic sizes of the two countries, probably simply do not exist. Romanian authorities are trying to promote wine products through the participation to several expo throughout China and the local consumers appear to appreciate Bucharest’s alcoholics.During a visit to Bucharest, Li Changchun, then member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China, declared his appreciation for the Romanian wine in the following terms: “at the welcome banquet hosted by the Romanian government, I had the honor to taste the Romanian made wine. My Romanian friends told me that Romania has a history of winemaking as long as France has. In the eyes of Chinese consumers, however, all they know is Lafite of France, not the wine of Romanian origin. Fortunately, it is still not too late, as the 800 million Chinese farmers have just begun to drink wine. Since they are not yet very Lafite-conscious, opportunities for Romanian wines to enter into the Chinese market are still available. I do not know the exact output of Romanian wine per year. But even if the 800 million Chinese farmers each consume only one bottle of Romanian wine per year, the wineries in your country would find such demand impossible to satiate”. Despite Li’s optimism, however, the competition from French, Italian and even Moldavian products, together with the development of the local industry, give a hard time to the Romanian efforts.

Graphic 2. China-Romania trade, 2000-2010. € Million.

Data source: Institutul Naţional de Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 2006; Institutul Naţional de Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 2007; Institutul Naţional de Statistica, Anuarul Statistic al României 2011, p. 573; Corneliu Russu, Marius Bulearca, “Chinese Economic Reform and the Romanian-Chinese Economic Relations”, in Buletinul, Universitatii Petrol-Gaze din Ploiesti, Vol. LXI, no. 4, Seria Stiinte Economice, 2009, p. 50. http://www.upg-bulletin-se.ro/archive/2009-4/6.%20Russu,%20Bulearca.pdf.

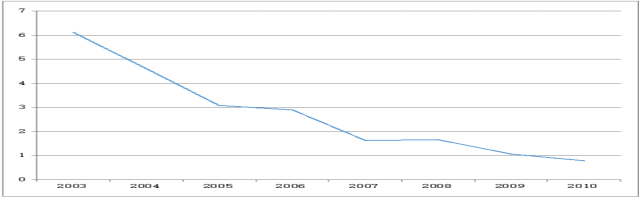

Graphic 3. Stock of non-financial Chinese FDI in Romania, 2003–2010. $ Million.

Data source: MOFCOM, 2009 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment,http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/hzs/accessory/201009/1284339524515.pdf; MOFCOM, 2010 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment, http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/hzs/accessory/201109/1316069658609.pdf.

Graphic 4. Decline of Romania’s quota in Chinese FDIs to Europe.

Own elaboration of MOFCOM data.

The bilateral economic relationship goes further beyond the trade realm and interests the foreign direct investments (FDI) field. Once again, it is a one-way argument, with the flow of Chinese investments toward the Balkan country to which do not correspond a similar flux of Romanian investments to the Middle Kingdom. Despite the potential, however, the Chinese FDIs stagnate and experience some problems. At the beginning of the Nineties, because a flexible local regulation on the argument that allowed the Chinese migrants to open many enterprises with a small amount of capital, Romania was among the top recipient countries of China’s investments. This situation leaded to a high number of Chinese enterprises but a tiny invested capital.

At the end of the first decade of 2000s, the main enterprises operating in Romania with Chinese capital were:

Golden Way BV, with a capital of € 28 Million.

China Tabacco International Europe, with investments for $ 35 Million and perspectives to arrive to $ 100 Million.

Eurosport DHS, bicycle producer, with € 20 Million investments.

Dongguan Yuncheng Plate Making Co., a company from Guandong, which invested $ 4 Million in the Prahova province.

Rich Sport, bicycle producer that invested $ 3 Million to open a production site in the Ialomita province.

F&J Romania, with investments for $ 15 Million.

The above listed company are medium enterprises involved in manufacturing of low-tech products. During the fall 2009 the company Shantou Agricultural Machinery Equipment opened a tractor firm in Rașnov. The investment amount to € 20 Million with prospects to reach € 50 Million in three years. Other achievements involve the renewable power sector, in particular the construction of solar panels. In 2012, the Chinese company Renesola bought the Romanian Lucas Est and had almost completed a photovoltaic park in the Prahova province. Further Chinese companies has showed interest in the field. In the IT and communication field, both Huawei and ZTE have gained some contracts and opened offices in Romania.

During the first decade of 2000s, Romanian authorities continually declared the intention to profit from China’s new “going global” policy. The wishes, however, proved hard to realize. Romanian proposals mainly address the infrastructure and power fields. Indeed, the Balkan country still lacks a route and railway network comparable with European standards and have proved unable in properly use the funds provided by the European Union. Therefore, governments of different banners and colors met several times with Chinese companies’ representatives and political leaders proposing the involvement in various projects: the construction of nuclear reactors no. 3 and 4 of the Cernavoda plant, the construction of the hydro-electric plant of Tarniţa-Lăpuşteşti, the carbon plant of SE Doiceşti, the Rovinari complex, the modernization of the “Dimitrie Leonida.2 plant of Bicaz, the modernization of the port of Costanţa, the construction of the highways segments Sibiu-Pitești and Comarnic-Brașov, the construction of a bridge in Braila and the construction of river canals on the Danube. The proposals could involve the following Chinese companies: China Huadian Corporation, China Coal Technology & Engineering Group Corporation, China State Grid International Development Ltd., Sinohydro, China Nuclear Power Engineering Co. Ltd., China Gezhouba Group International Engineering Co., China National Agricultural Group Corporation, China Communications Construction Company, China Dalian International Holding, etc. The Romanian side also proposed to ZTE and Huawei companies buying shares of the national state-owned company Transelectrica. None of these proposals concretized. Furthermore, various attempts from Chinese companies to invest in Romania failed. China Huadian Engineering, China National Electric Engineering, Minmetals Engineering Co. Ltd. and Sinohydro, for example, did not reach even the final stage of an international competition launched by the Russian-Dutch group Vimetco to realize a thermoelectric plant for supplying power to the aluminum production plant of Alum Tulcea, a second plant of Alro Slatina and the city of Tulcea.

The consequences of these failures are explicated by the decrease of Romania’s role as recipient of Chinese FDIs in Europe (Graphic no. 4). Indeed, the moderate increase of Chinese investments in the Balkan country was much lower of the broader growth of Beijing’s FDIs in Europe. Considering China’s interest in access the Western EU member’s markets, Romania’s unfavorable geographic location, which does not allow a rapid transit of products to Western Europe, may be a motivation of this situation. Then Chinese Ambassador to Romania, Liu Zengwen(刘增文), also outlined the difficulties deriving from the strictly binding EU legislative framework on matters of labor force to which Romania must adhere and respect.

According to the China Radio International journalist Dan Tomozei, however, the cause of the lack of Chinese investments in Romania is entirely on the shoulders of Bucharest’s leadership, guilty of not dedicate enough interest and care to the relations with Beijing. Tomozei explicitly charges Romanian politicians, not capable, in his view, to understand China’s art of diplomacy and culture, therefore incurring in misunderstandings and gaffes. Moreover, former President Traian Basescu lined up with the US and continually obstructed any approach to Beijing by releasing rash declarations. This was the situation of the Sino-Romanian relationship when the social-democratic leader Victor Ponta accepted the role of Prime Minister in May 2012, after some street protests occurred in the previous winter due to the economic crisis and the austerity measures taken by the government.

The Ponta’s premiership and Sino-Romanian relations

According to Dan Tomozei, the new Romanian Premier could claim good connections with some Chinese administration and Party officials; moreover, his nomination attracted an unusual attention of the PRC’s media. Indeed, his government showed a moderate dynamic in taking care of the relations with China. In September 2012, the Ministry of Agriculture, Daniel Constantin, met with the Chinese vice Minister of Agriculture, Niu Dun. In October 2012, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Titus Corlăţean, met with the architect of China’s foreign policy, Yang Jiechi. In the summer of 2013, Ponta met with both President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang.

The partial data from the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ website, however, show a negative trend of the bilateral trade during the first year of Ponta’s government. Indeed, the bilateral trade reached its apex in 2011. That year, import and export both touched their climax. Romanian negative balance of trade, however, diminished a little respect to 2010. Starting in 2012, the stagnation of Romanian economic and the slowing down of China’s economy affected the commercial exchanges. Both Romanian import and export decreased, but the balance gap between them appears narrowing. The trend highlighted in table 1 suggests that the only possible way to limit the disequilibrium of the Sino-Romanian balance

of trade is to reduce the exchanges to minimal terms.

Tabel 1. PRC (Hong Kong excluded)-Romania trade, 2010-2013. $ Million.

Year Total Trade Romanian Import Romanian Export Balance

2010 3,893.41 3,394.55 498.86 - 2,895.69

2011 4,201.86 3,542.58 659.28 - 2,883.30

2012 3,180.00 2,680.00 500.00 - 2,190.00

2013 (10 months) 2,389.46 1,905.43 484.03 - 1,421.40

Source: Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs http://www.mae.ro/bilateral-relations/3121#759, last update January 2014, last access 28 January 2015.

Despite this critical data, the Sino-Romanian relationship substantially improved when Bucharest hosted the China-CEE annual meeting at the end of November 2013. Premier Li Keqiang arrived in Romania to attend the summit 19 years after the last visit by a Chinese Prime Minister in Bucharest. Romanian authorities gave a royal welcome to Li and the Chinese delegation could talk with representatives from 16 CEE countries. In response, Chinese Premier adulated the Romanian host, by saying that “Romania will become Europe’s tiger and if all tigers join and communicate a huge market will develop”.

At the end of the Premier meetings, the involved sides adopted a joint statement called “Bucharest Guidelines” that should address the bilateral relationship China-CEE countries. According to the document, 2014 will become the year of the promotion of investments and businesses within the China-CEE countries relationship. The document promotes the organization of economic forums and summit meetings. It highlights the need to encourage small and medium companies within cooperation between the two areas, to develop agriculture cooperation, to promote financial institutions for cooperation and full capitalization of special financing of US $ 100 billion, which China laid at the disposal of countries in the sector, to consolidate cooperation in investments and infrastructure, above all on railway networks. The fields of science, technology, innovation, environment protection and energy, culture will be interested by a new strengthen collaboration. Indeed, Chinese and Romanian sides has signed several economic agreements on that occasion, involving both railway infrastructure projects and the energy sector, the implementation of a Technology Park, the Romanian export of meat and livestock to China. The Complex Energetic Oltenia signed an agreement with China Huadian Corporation above the thermoelectric plant of Rovinari; similarly, the Complex Energetic Huneodara signed an agreement with China National Electric Engineering in reference to the implementation of the thermoelectric plant of Deva. The Romanian company Paunescu Corporation signed an agreement with the Mingyang Wind Power Group in the eolian field. The Sinohydro Corporation has manifested interest on the hydroelectric plant of Tarniţa Lapuștești; BAOTA Petrochemical Group and JUNLUN Petroleum Co. are available to buy the Oltchim petrochemical plant.

Eventually Li Keqiang’s visit deeply influenced the internal Romanian political debate on foreign policy and the Summit as a whole has been commonly interpreted as a Victor Ponta’s success, sharpening the previous split between the Premier, who appears reproducing the policies previously adopted by former Prime Minister Adrian Nastase, and President Basescu.Nevertheless, once again the Romanian government appeared unsuccessful to exploit the political success of the Bucharest Summit. Also considering Basescu willingness to fight back any attempt to get closer to Beijing, Ponta probably avoid re-launching the efforts to enhance the relationship with China. Moreover, the Prime Minister focused his attention and efforts on running for the presidential elections. In such a context, foreign policy was not a hot topic of the electoral campaign, mainly concentrated on internal affairs and corruption scandals. Suddenly, the right-wind liberal Iohannis defeated Ponta. Therefore, weakened in his position, Ponta had to play an apparently secondary role at the subsequent China-CEE Summit held in Beograd at the end of 2014.

Romania’s presidential elections seen by China’s Xinhua press agency

China’s Xinhua press agency gave moderate attention to the race for Romanian presidential elections, starting with the nomination of Klaus Werner Iohannis as chairman of the National Liberal Party and main opponent of current Prime Minister Victor Ponta. The elections were set for 2 November 2014. According to several opinion polls, Ponta was the favorite for the presidential elections. Xinhua diligently reported the polls’ ratings and avoided to make any comments on them. Chinese vice Premier Zhang Gaoli visited the Balkan country during the electoral period and met with Ponta. Discussions, however, centered mainly on economic matters and future opportunities for the bilateral relationship. The Chinese official kindly and diplomatically avoided any reference to the electoral race.

At the down of the first round of the elections, Xinhua analyst Lin Huifen underlined that Ponta had concrete chances to succeed but the eventual second round of vote could result in some surprises, considering the possibility that the rightist-liberal front could coagulate on the figure of Klaus Iohannis. Moreover, the Chinese analyst reported the several scandals that affected numerous representatives of both the fronts. Indeed, Ponta actually won the first round of the elections but did not reach the necessary majority to avoid the run-off two week later\. The first round of elections, however, were characterized by many voting amenities for the overseas Romanian diaspora. The emergence of this issue led the Romanian Foreign Minister Titus Corlatean to his resignation. Premier Ponta replaced him with the former Foreign and Defense Minister and Head of Foreign Intelligence Service, Teodor Melescanu. President Traian Basescu agreed to the nomination but only because the urgency of the situation and publicly expressed his personal disappointment with the appointment. Quoting Romanian analysts, Xinhua noticed that these events could negatively affect Ponta’s race to the presidency. In fact, Iohannis won the second round of the elections with 54.66% of the votes, despite several Romanians abroad could not vote once again, originating some violent clashes in Paris.

On 21 November, Xinhua agency published some excerpts from Iohannis’ speech given during taking his presidential oath of office in front of the bicameral Parliament. The excerpts focus on the promise of efforts to make Romania a more unite country and to fight corruption. Indeed, Romania is one of the most corruption-affected country in Europe. It is easy to note that the excerpts chosen by Xinhua are not casual. Country’s unity and fight to corruption are among the main topics of China’s current government.

On 22 November, the Chinese press agency reported the confirmation of the electoral results by the Romanian Constitutional Court with few aseptic sentences and two photos. Xinhua also noted that Iohannis would take effective power only at the end of Basescu’s mandate in mid-December.

The election of Klaus Werner Iohannis: what are the perspectives for Sino-Romanian relations?

Once again, the evolution of Sino-Romanian relations will much depend on Bucharest’s willingness to get close with the Asian giant. After the events of December 1989, indeed, Romania totally turned its attention to the West, European Union and US. Russia became a sort of bogyman for the Balkan country, while China was simply out of Bucharest’s foreign policy radar. In fact, under the presidency of Traian Basescu, Romania became one of the closest European allies of the US, despite its negligible offer in terms of military contribution and minimum political leverage in the international arena. Its geo-strategic position, however, has been important for US moves directed to contain Moscow’s resurgence as a main regional player.

As we have seen, in recent years, several Romanian governments tried to approach Beijing in order to look for investments capable to boost Bucharest’s staunch economy. These attempts, however, never ended with concrete outcomes. Despite China displayed its willingness to invest in the Balkan country, a mixture of misunderstandings and reciprocal diffidence had built insurmountable obstacles. Moreover, Romania showed a sort of self-restraint in approaching China, in order to do not create alarm to its powerful Atlantic protector.

Ponta’s rise to the premiership originated new expectations and the China-Central Eastern Europe summit held in Bucharest in November 2013 was a great success for the Socialist Prime Minister. Nevertheless, such expectations showed to be beyond reality, once again.

Nowadays, the election of the liberal Klaus Iohannis to the presidency represents a new challenge to Sino-Romanian relations.

Before the run-off of 16 November, Iohannis stated that Romania had “the opportunity to irreversibly take the road of Western values”. Xinhua punctually reported Iohannis’ statement, which may alarm who give high priority to the relations with East, including China. Iohannis, however, also called to withdrawn “all ambassadors and consuls from those countries where Romanians were humiliated” and “treated with tear gas because they want to vote”. Considering that the clashes happened in EU countries, the new President’s declaration is in sharp contrast with its main orientation to West. Once he took effective power, however, Iohannis released some Western-oriented declarations, which have been immediately noted by Xinhua. Following the dramatic events in Paris, the new Romanian President assured “all partners of Romania of the full support in the fight against terrorism and extremism of any kind”and called for closer ties with the United States.

What is sure is that the cohabitation between Prime Minister Ponta, who in the aftermath of the elections announced to be determined to remain in charge of the premiership, and President Iohannis will not be easy. Nevertheless, Iohannis immediately reached an agreement with all the political parties of the Parliament in order to increase the Defense budget.

Eventually, considering the current European political environment and the Ukrainian crisis close to Romanian borders, the elaboration of new directions in the foreign policy strategy appears quite unlikely. The bilateral relationship with China, therefore, will likely continue on a path of political and economic ups and downs, staying far behind the level of diplomatic and economic exchanges that Beijing has reached with other CEE countries such as Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and even Slovak Republic and Serbia.